Inflation Is Here

The classic definition of inflation prattles on about rising prices for certain goods (or a basket of goods) and the declining purchasing power of money.

I’ve never found that very helpful. Because prices for stuff don’t just rise magically. And the relative value of a dollar doesn’t fall out of the blue.

The price of stuff and the value of money ebb and flow. And like the tide, they do so because they are acted upon by an outside force.

Supply and demand are what make prices and value change. When people want a thing (demand), we say it is valuable and the price rises. And when people want to get rid of a thing (supply), we tend to think it’s useless and no one wants it.

That’s getting better. It speaks a little more to exactly why we get inflation. But it doesn’t really help with the kind of inflation the Fed worries about.

In other words, I’ve never heard the Fed worry about the price of baseball cards, art, or wine going up. Because we understand why a Cal Ripken baseball card was suddenly worth more after he broke Gehrig’s consecutive games streak. We also get that a certain percentage of those little pieces of cardboard will get wet, folded, or lost over time. The survivors get a rarity premium…

When I was first starting out in this biz 20 years ago, somebody taught me that inflation is “too much money chasing too few goods.”

Or, to get all academic on you, here’s the Milton Friedman quote:

Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output… A steady rate of monetary growth at a moderate level can provide a framework under which a country can have little inflation and much growth.

And it’s this definition that justifies the Fed’s policy decisions. Or at least it should…

Blind Mice

Before the U.S. had the Federal Reserve, it had banking panics all the time. In 1873, 1893, and 1907, the whole country was gripped by banking panics. The banking panics of 1884, 1890, 1899, 1901, and 1908 started in New York City and spread only locally.

In 1896, a regional banking panic hit Illinois, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Pennsylvania and Maryland had their own panic in 1903. The Panic of 1905 was just Chicago.

That first one, 1873, started with railroad investments. A stock market crash in Vienna forced a bunch of big investors to raise cash. When they went to sell investments like U.S. railroad bonds, it drove prices lower. Railroad companies suddenly couldn’t fund operations, so they defaulted or went bankrupt. Confidence in banks that financed railroads fell. They couldn’t get cash, and over 100 failed. The NYSE closed for 10 days.

Sounds a lot like the housing crash of 2008–09, doesn’t it?

The creation of the Fed in 1913 ended these frequent bank panics. Basically because the Fed makes sure banks have access to cash pretty much anytime. And the Fed gets to make sure banks meet reserve requirements before it will lend them money.

If that was all the Fed did, great. It would probably work pretty well. But somewhere along the line, it seemed like a good idea to let the Fed try and manage supply and demand by adding and removing cash from the system. That’s bad. But believing that you can actually do this (as a Fed member must) is worse…

Back in 2005 and 2006, Fed Chief Greenspan thought he had it all under control. He was raising rates slowly. The economy was strong but not overheating. People’s houses were appreciating nicely…

Greenspan thought the rise in home values was a pretty good thing. He saw a house as an asset, and this meant Americans were getting wealthier. How could that be bad?

Greenspan didn’t realize it wasn’t real value like a Cal Ripken card (if we can call that real value). He didn’t see the housing bubble as inflation because he thought he was controlling the money supply. But the banks were creating a ridiculous amount of money by basically eliminating lending standards and then securitizing and selling mortgages (when we hear the term “securitize,” it’s just that something has been turned into an asset that can be easily bought or sold).

Absolute Power Corrupts

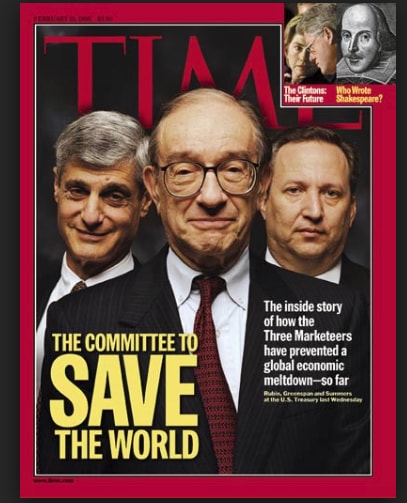

This was the Time magazine cover on February 15, 1999:

Look at the little smirk on Greenspan’s face. You telling me he doesn’t believe the hype? Yeah, he’s got it all figured out…

The man’s timing was great. He retired less than two years before the worst meltdown since the Great Depression. I still don’t think he understands where he messed up.

His successor was equally arrogant. Ben Bernanke dumped like $4 trillion into the U.S. economy. He did it to keep rates low so that maybe people would borrow money to buy stuff and then maybe the companies would see demand and make more stuff and hire more people to do it and then we’d get a little inflation going.

Stay on top of the hottest investment ideas before they hit Wall Street. Sign up for the Wealth Daily newsletter below. You’ll also get our free report, Investing in the Vix: 3 VIX Funds to Own Now.

After getting your report, you’ll begin receiving the Wealth Daily e-Letter, delivered to your inbox daily.

Once again, we have a Fed Chair (pretty sure Bernanke taught at Harvard) who doesn’t understand a basic economic principle of supply and demand. And that is that money is not demand. Sure, it may represent demand. It may actualize demand. But the two are not synonyms.

Bernanke didn’t get the dollar to lose value. And he never got his inflation indices to show much. And GDP (a decent measure of demand) barely moved.

But there are signs that he may have had more success than it seems. Just not where you’d expect to find it. I mean, we’ve sure had a stock market rally. The federal deficit has exploded higher.

Check out this table:

Oh yeah, there’s no inflation. Just 80% of houses in San Francisco cost a million or more…

Former Fed Chief Yellen had to start hiking rates. Current Chief Powell was right to continue. It’s time he stopped and looked around for the places that have gone from inflation to scary bubble.

Home base for the biggest companies (San Francisco) in the world is a housing bubble. 80% of last quarter’s 3.5% GDP growth was government spending. The stock market is ~12% from all-time highs as a trade war threatens to crush earnings…

The market is worried. The Fed should be, too.

Until next time,

Briton Ryle

The Wealth Advisory on Youtube

The Wealth Advisory on Youtube

The Wealth Advisory on Facebook

The Wealth Advisory on Facebook

A 21-year veteran of the newsletter business, Briton Ryle is the editor of The Wealth Advisory income stock newsletter, with a focus on top-quality dividend growth stocks and REITs. Briton also manages the Real Income Trader advisory service, where his readers take regular cash payouts using a low-risk covered call option strategy. He is also the managing editor of the Wealth Daily e-letter. To learn more about Briton, click here.

The Best Free Investment You'll Ever Make

We never spam! View our Privacy Policy

After getting your report, you’ll begin receiving the Wealth Daily e-Letter, delivered to your inbox daily.

@BritonRyle on Twitter

@BritonRyle on Twitter